Fyerool Darma (b. 1987, Singapore) works predominantly in painting. He focuses on the absent history of Southeast Asia mainly to understand migration, politics of identity and post-colonialism. He lives and works in Singapore.

Interview with Fyerool Darma

***

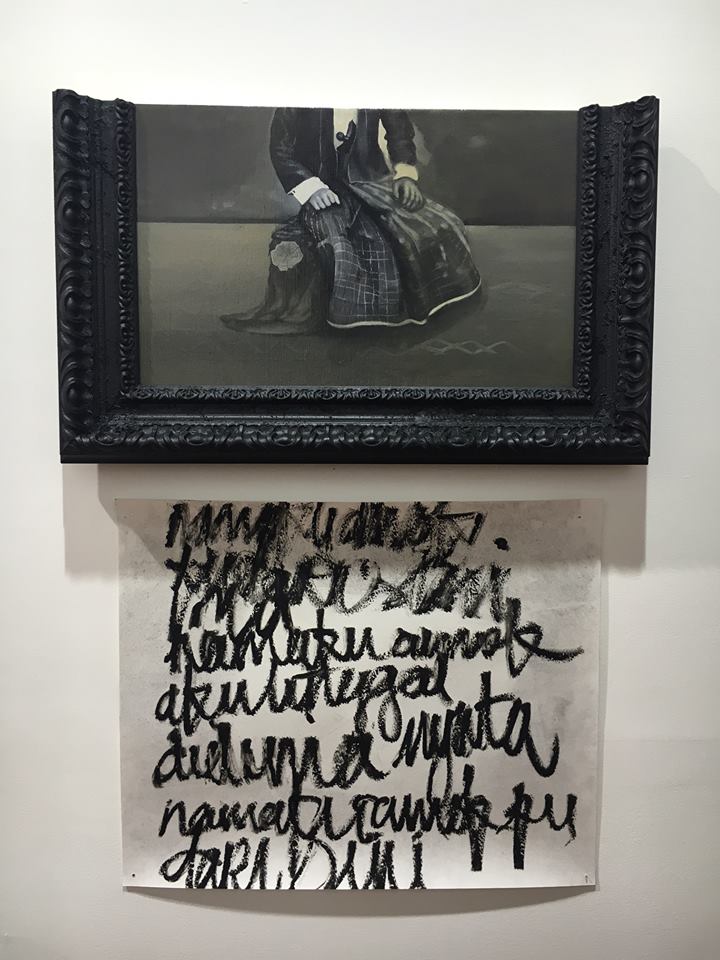

Nijvest (N): Tell us more about Portrait No. 9 (Si Mata Pena) of Moyang series. What inspired this series?

Fyerool (F): It is from the series – Moyang, or ancestors in English but the painting does not take its direct meaning nor familial baggage. It was a way to locate the growth of a language and its speakers, where I was exploring on the idea of ‘one from the same tree’. I am still navigating in the sea where attributes of identity and language within this region is constantly eroding, as such in other parts of the world. In this series too, I disregard ones’ social statuses and class, hence the obliteration.

There exist the movements of individuals from a specific society way before the 1800s, also some were moving or forced to be part of the slave trades then. In South Africa, in Cape Town there is a Malay district though none there speaks the Malay language, they still do identify themselves with the culture, literature and dishes. They speak Afrikaans. Also, in Sri Lanka there are a lot of Malays but they also do not speak the language.

My interest lies in understanding the movements and languages of individuals from this specific society that is also part of the Asian dynamic. When we look at languages, they represent transformations, growth and collision from a mark.

This is a portrait of Raja Ali Haji, who was one of the rulers from Riau which Singapore was part of, in the 1800s. During his reign, one of the kings from France gifted a press machine to him. That was the spark of the intellectualities within that society and how it spread around. The bottom piece is a separate piece but from how I see it, it is an assemblage of all my thoughts.

It is a scribble that was inspired from Chua Mia Tee’s painting, “National Language Class”. The text was a rethought to the question that he wrote on his painting. He wrote, “What is your name? Where do you live?”. What I wrote in Malay was “Namaku Amok. Aku dari sini.” (My name is Amok. I’m from here). I wrote amok out of impulse too. It reflects too of life, it also is one of the words that exists in the English dictionary that has it’s roots from a language – Malay.

For the demarcation of Raja Ali’s face, I thought it was cool. But apart from that, I used it as a way to reflect back on the adage – ‘Harimau mati meninggalkan belang, manusia mati meninggalkan nama’ (A tiger passes on leaving his stripes, whilst men leaves his name.)

Through that, I understand from a name, deeds are remembered. A name too has meaning just like words, texts. Sacred they are. Apart from aesthetic itself, it’s about going back and giving significance to the benevolent who has passed on by just focusing on the his name (title to the work) and a allow individuals not to be distracted by his features but rather his deeds (hence the hand).

Fyerool’s interest is in the locating of culture. He is presently based in Singapore, whose work was included in the Singapore Biennale 2016: An Atlas of Mirrors at the Singapore Art Museum.

Portrait No. 9 (Si Mata Pena) of Moyang series

N: Tell us about your background. You were born in Singapore and raised in an artistic family?

F: Oh no, nobody in my family did visual art. Some were musicians, but craft were at their core in their everyday. From September 2016, I conducted oral interviews with the elders in my family starting from my maternal grandfather and found out, he used to produce textiles in his home.

He produced stamp batiks with a stamp that is made from brass gifted after a class he went. He produced batik prints but would not consider himself an artist. He mentioned, he looked at it as a means to generate income. He continued for several months only to sustain his new family then, this was soon after the Japanese rule.

I graduated from LASALLE College of the Arts. Before that I was studying at Siglap Secondary School. It was there that I got expose to paintings, Siglap had a collection of Indonesian Masters, like Affandi and Baseoki Abdullah, but perhaps they were knockoffs. Then I did not give much attention to them. I spent 6 years in Siglap. I chose that school primarily because I was fearful of going to a different route alone and did not want to be separated with my twin brother.

N: What did you study in school?

F: In school I studied painting. LASALLE was transiting from the old campus to the new campus. They had no specialise discipline but I was encouraged to experiment with many other materials. Even within painting itself, we were taught to not look at painting as a painting but to go beyond that and to look at other materials to think and differ. It is always a question of challenging whatever is there.

I too learnt several new mediums like aerosol and was exposed to ssubcultures from friends who were greatly involved in them when I was in my teens. Mediums like zine-making, wheat-pasting, scratchiti, stencil to o the use of industrial paints; aerosol, enamel or emulsion.

N: What brought you about to paint and create art for a political message? Were you taught that or did something outrage you that you had to express it this way?

F: I was not outraged at all. It was impulsive but a reflection came gradually after.

2 years after LASALLE in 2014, I was at my studio in Ubi Industrial Estate and one day I just cut a portion of a painting that I was working on for the past 5 months. Coincidentally, it was the seventh month, and there was an incinerator bin at the ground floor where the joss papers were burnt as offerings. After observing the processions and offerings, I brought all the paintings down to the ground floor and threw the works in the incinerator bin.

Reflecting on it, in that moment, I wanted to erase the works immediately for reasons to today I am still asking myself. Perhaps it was of insufficient interior space too. Someone too asked me if I’d think of it as a way of me offering paintings to my ancestors, perhaps I was but I did not think of such then.

N: Why did you burn your work? When you create something, isn’t it like a child or giving birth to a child?

F: It was really impulsive in that moment. It became easier gradually. Several weeks after that, I realized it was a process I needed. It was a process that brought me to these present works, to my present interests in the subjects that I am focusing into. The burning also created a distance for me from certain events or happenings in my life. I think I am more attached to the process rather than the product of that process.

I realized I was gradually unravelling the mess and curiosities that floats in my mind. Like one; my dad enjoy sharing stories of his father who came from Java, and survived the Japanese occupation. I never met my grandfather too, he passed on just after my mother gave birth to my eldest sister. There is always a question about how true these narratives are, especially when they run through the family history.

So, it was an investigation into that and just out of curiosity. I was thinking about the possibilities and all the probabilities that exist within these oral histories.

In a way too, the act paved me to understand that within time, several aspects of life and its narrative changes.

It made me realise the eradication and erasure of collective memory exists constantly; what ‘we’ want/should remember in contrast to what ‘we’ should or wishes not to remember. Like a child too, you let them grow on their own with the values you’ve impart on them and not be too attached.

N: So, that was you cleansing experience in a sense?

F: In a way yes.

N: Did that help you find your way to a new you?

F: Yes, burning symbolises one of that aspect; rebirth and rejuvenation in several Southeast Asian and Asian Culture, as well as other societies in the world. Darren Aronofsky, puts it beautifully, ‘Death is the road to awe.’

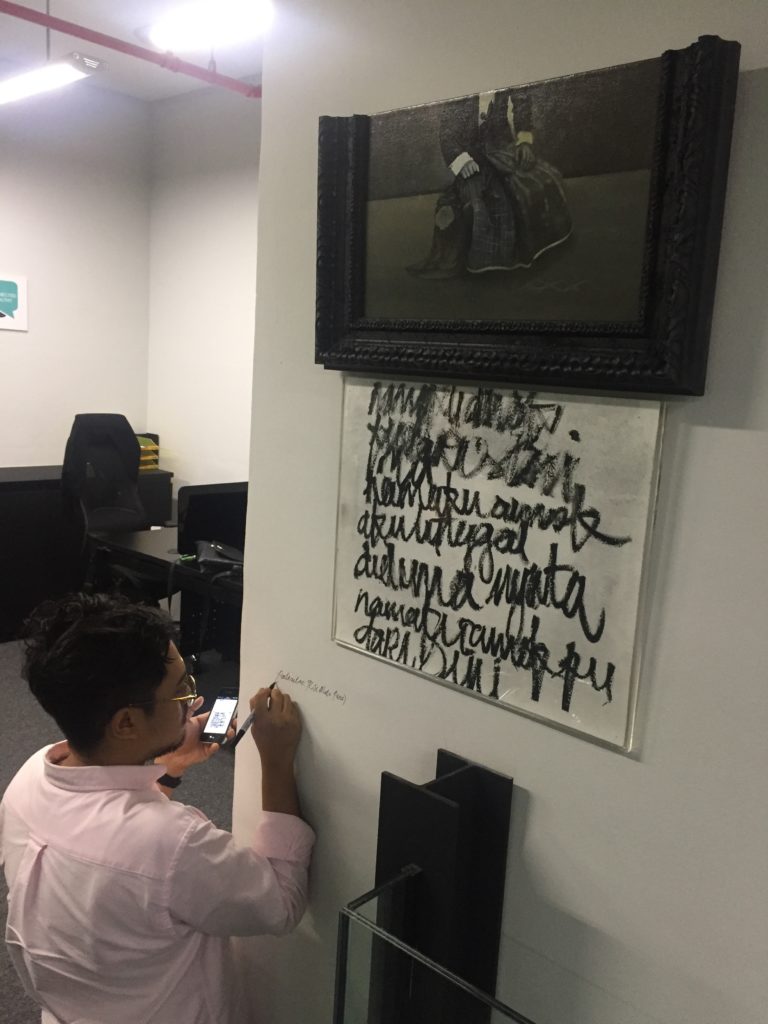

Fyerool signing on the wall below his art piece

N: Are you a full-time artist?

F: Yes, I am presently a full-time artist. I made a leap, I used to work as a technician in a gallery, institution and was also in a production studio. I wanted to learn new things to unlearn what I learnt from college. I realized soon after I graduated, the works I produced and burnt were self-indulgent. Having to discipline the self to attend to the day job and practising art, it allows me to look at things differently, and give more respect to time. I was constantly asking myself of the artist role in the present time, society and his or her geography.

N: Do you consider yourself a Singaporean or a Malay Singaporean?

F: One thing that is interesting about that question is how we perceive and continue discussing on the ideas of identity; in parallel it’s still a trivial question as to which category I consider myself in.

I think personally, I still am interrogating myself if such categories are necessary, here and in the world. I consider myself a human, like each and every one – an individual.

Those terms to me are classifications again that group certain individuals to a box. But for whom? Differences makes us understand certain things easily but it could fall in the habit of comparisons and that is when it becomes a problem.

N: Have you noticed that the older generation of Singaporeans are more self-contained and not so open whereas the youth are much more open?

F: I think it’s about the current state of things in this present moment; the internet really does help with that perceptions. The internet breaks this idea of classifications in a way. And the internet is a place where nationalities, race and groupings as such need not exist. I do talk to several older generations of Singaporeans, surprisingly they are not reserved but rather do share their thoughts and experiences. Several are strong with their thoughts and beliefs too, but off course, there are different manners in speaking with the elders. To which, I find admirable – this diverse manners of speaking to different individuals.

N: Do you mostly hang out with Malays?

F: No and yes. Whoever. I have close friends who are Chinese but they are the most Malay, they know more Malay, its culture, politics, history and language more than me too, even to its pop songs. They speak Bahasa Melayu to me. It feels weird yet nice. There was an instance where two Chinese speaking individuals spoke to me in Malay in front of me and I asked them why can’t they speak English instead? But they were more comfortable in that language.

But they both speak that language fluently and understands it well, they were born, raised and studied in Singapore schools too. But it was their exposure to certain subcultures and the integration with other individuals too.

N: Do you have a different identity between Malays here and in Malaysia?

F: When we talk about identity it goes back to the way they speak, the grammars they use. They have a different manner of utilizing the language and it differs too from geographies. Borders are what differentiates individuals too, at the same time, it creates the limitations to what they would be recognised for collectively indefinitely.

So in a way, we are different from the experiences of our local, the perspective we view several aspects of society, in Singapore, this certain individuals are part of the minority, whereas in Malaysia, they are the majority – that is the first difference, you look at the world and your surrounding in a different view when you are in different dynamics as such. There are the advantages too when you are part of the majority. Then again, the similarities of us all individuals are that we are humans after all.

N: The topic you are concentrating on, about historical amnesia is very interesting but it is very local. Have you ever thought about making that topic broader since every country has it?

F: It’s a human condition when we think of it – forgetting/remembering, erasing/preserving, memory/amnesia or wisdom/ignorance. At the same time, the geography or nation/s and the politics that exists of the space/s also contributes to that amnesia. What makes this body of works ‘local’ is how we choose to identify with its location and the production of the work. I think it does speak borderlessly – these individuals are of individuals from a specific space but in today’s context, they are of individuals from a different country. That in itself is broad, only contextualising it makes it specific to its geography, place and here, locality.

N: How do you find your community?

F: It has always been around me, but I was ignorant of its presence the longest time.

N: What’s next?

F: In the coming series, it’s a reflection of my process in locating culture. Within that enquiry, I realized there’s a collision or hybrid of several cultures as well.

It is also a way of me interrogating my own perceptions of what beauty is by accepting its aesthetics and understanding the manners and ways in which it is produced; the ‘beauty’ that I grew up being expose to that I was too ignorant in accepting. In short, it is the process after the burning – the rejuvenation of that.

N: Thank you for this really interesting conversation.